LXVI

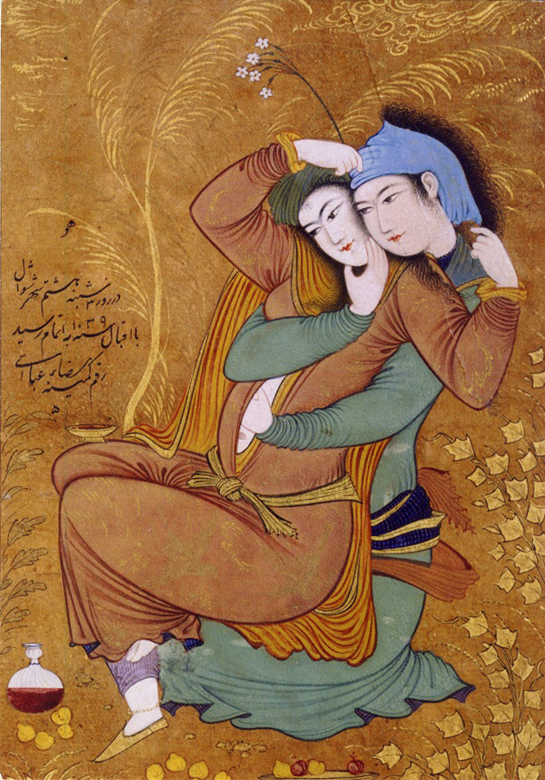

Western scholars of the nature and character(istics) of mysticism have described two modes: extrovertive and introvertive. According to H.D. Roth in Original Tao: Inward Training (Nei-yeh), the former “looks outward through the senses and sees a fundamental unity between this individual and the world, simultaneously perceiving the one and the many, unity and multiplicity.” This mode has been called “cosmic consciousness.”

“Introvertive mystical experience looks inward and is exclusively an experience of unity, that is, an experience of the unitive or what some scholars… call ‘pure’ or objectless consciousness.”

And, of course, the question arises, time and again, as to how the mystical experience is culturally mediated, or even predicated upon pre-existing and internalized religious and other categories. Or, whether mystical experience “strips away” any and all of these underpinnings or referents.

And yet, the sparrows.

And stonemasonry. The stonemason. Electricity and the electrician. And nestled among these earliest and the latter-day trades: the writer.

She lives on Grubb Street, lingers long on Grubb Street…

Be short. Belong. Be strong. Betrade.

Befit. Befoul. Bestride. Befall.

Behead. Behold. Bewild(er). Beetroot.

When is the trade not the work?

Sister Writer: can you lay your courses row on row without recourses to the portland cement of plot?

Brother Writer: do you check your level against the plumb bob? And break the former over the topmost stones when it lies to you? Which it will. Because it is subject to forces to which your plumb bob is not. Your plumb bob has only got one place it can home to, and that place is four thousand miles beneath the square of your feet.

What about the work is not the work?

Are not the introvertive and extrovertive – in mysticism as in all else – reciprocal motions of the breath?

Neither a servant nor a master I,

I take no sooner a large price than a small price, I will have my own whoever enjoys me.

I will be even with you and you will be even with me.

If you stand at work in a shop I stand as nigh as the nighest in the same shop.

If you bestow gifts on your brother or dearest friend I demand as good as your brother or nearest friend.

If your lover, husband, wife, is welcome by day or night, I must be personally as welcome.

If you become degraded, criminal, ill, then I become so for your sake,

If you remember your foolish and outlaw’d deeds, do you think I cannot remember my own foolish and outlaw’d deeds?

If you carouse at the table I carouse at the opposite side of the table,

If you meet some stranger in the streets and love him or her, why I often meet strangers in the street and love them.

Why what have you thought of yourself?

Is it you then that thought yourself less?

Is it you that thought the President greater than you?

Or the rich better off than you? or the educated wiser than you?

(Because you are greasy or pimpled, or were once drunk, or a thief,

Or that you are diseas’d, or rheumatic, or a prostitute,

Or from frivolity or impotence, or that you are no scholar and never saw your name in print,

Do you give in that you are any less immortal?)

[From Whitman, “A Song for Occupations,” Book XV, Leaves of Grass]

Not quitting, not sticking.

Once, a dozen winter solstices ago, you passed through the Medieval “nave” at the Met where the Neapolitan Christmas tree was being assembled, and pausing saw, there, atop the narrow platform of a hydraulic lift, a young woman perched, dressed all in black. Standing beneath her on the flagstones, two older and more earthbound women, each holding a large photograph of the finished tree taken from their respective angles. They called out to her and gestured, and you watched, dumb as a ceramic ass, as the elevated woman stretched forward over the railing of the cherrypicker to place an angel just so among the boughs, then leaned back to take in what she’d done. A spotlight caught the oscillating current of her auburn hair and the crescent white of her cheek. That’s all.

History will resorb me.

I was a shout in the street for the FBI.

For as ever, what about the work is not the work?

The learn’d, virtuous, benevolent, and the usual terms,

A man like me and never the usual terms…

I bring you what you much need yet always have,

Not money, amours, dress, eating, erudition, but as good,

I send no agent or medium, offer no representative of value, but offer the value itself.

There is something that comes now and perpetually,

It is not what is printed, preach’d, discussed, it eludes discussion and print,

It is not to be put in a book, it is not in this book,

It is for you whoever you are, it is no farther from you than your hearing and sight are from you,

It is hinted by nearest, commonest, readiest, it is ever provoked by them…

The sun and stars that float in open air,

The apple-shaped earth and we upon it, surely the drift of them is something grand,

I do not know what it is except that it is grand, and that is happiness,

And that the enclosing purport of us here is not a speculation or bon-mot or reconnoissance,

And that it is not something for which by luck may turn out well for us, and without luck must be a failure for us,

And not something which may be yet retracted in a certain contingency…

[Whitman, “…Occupations”]

Q: Please tell us who your favorite authors, classical and modern, are and whom you have learned from?

B: Recently I’ve been concentrating more and more on one writer – Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy. Pushkin, I need hardly say, is a constant companion. I think that our budding writers do not spend enough time reading and studying Tolstoy – surely the most marvelous writer who ever lived.

I must say that when I read Hadji-Murad* a few years ago, I was shaken quite beyond description.

As I read Hadji-Murad again, I thought: this is the man one should learn from. Here the electric charge went from the earth through the hands, straight to the paper with no insulation at all, quite mercilessly stripping off all outer layers with a sense of truth – a truth furthermore, which was clothed in dress both transparent and beautiful.

When you read Tolstoy, you feel that the world is writing, the world in all its variety. In fact, people say, it’s all a matter of devices and technique. If you take any chapter of Tolstoy’s you will find great heaps of everything – there’s philosophy, death. And you might think that to write like this you need legerdemain, extraordinary technique, skill. But all this is submerged in the feeling for the universe by which Tolstoy was guided.

As a literary critic, I’m no good, I’m terrible. I must apologize for talking this kind of stuff…

From “Babel Answers Questions About His Work,” September 28, 1937, in Isaac Babel: You Must Know Everything, Max Hayward, trans., Nathalie Babel, ed. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1968. pp. 213-14.

* Tolstoy’s last novel, written 1896-1904 and published posthumously in 1911]

And still we disappear.

Old institutions, these arts, libraries, legends, collections, and the practice handed along in manufactures, will we rate them so high?

Will we rate our cash and business high? I have no objection, I rate them as high as the highest – then a child born of a woman and a man I rate beyond all rate…

List close my scholars dear,

Doctrines, politics and civilization exurge from you,

Sculpture and monuments and any thing inscribed anywhere are tallied in you,

The gist of histories and statistics as far back as the records reach is in you this hour, and myths and tales the same,

If you were not breathing and walking here, where would they all be?

[Whitman]

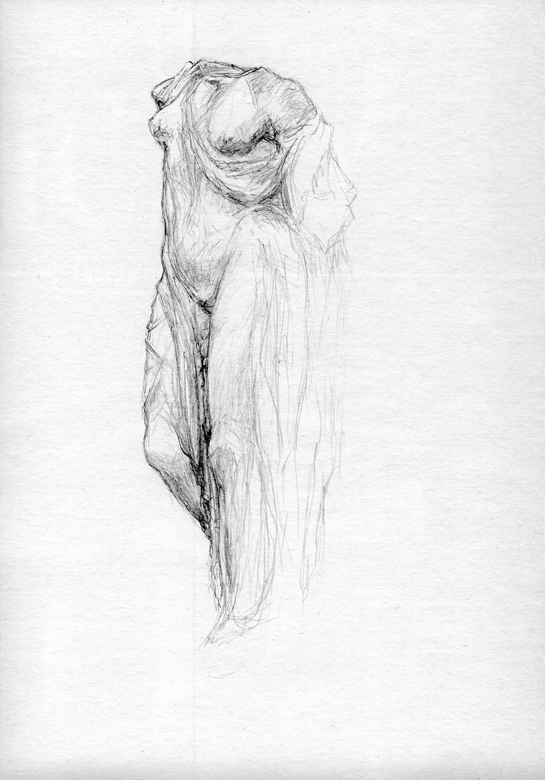

Genetrix walking. Or nearly so.

…a truth furthermore, which was clothed in dress both transparent and beautiful.

[Babel]

Strange and hard that paradox true I give,

Objects gross and the unseen soul are one…

All music is what awakens in you when you are reminded by the instruments…

When the psalm sings instead of the singer,

When the script preaches instead of the preacher,

When the pulpit descends and goes instead of the carver that carved the supporting desk,

When I can touch the body of books by day or by night, and when they touch my body back again,

When a university course convinces like a slumbering woman and a child convince,

When the minted gold in the vault smiles like the night-watchman’s daughter,

When warrantee deeds loafe in chairs opposite and are my friendly companions,

I intend to reach them my hand, and make as much of them as I do of men and women like you.

Again, and ever, “…Occupations.”