LXII

Extract from Notes of a New York Son:

October 9, 2002

Who knows exactly when, but definitely last night, amidst the potted lime trees in the Spanish Patio of the Metropolitan Museum, a larger than lifesize 15th century marble statue of Adam (grasping an apple) keeled over and shattered into bits large and small – in any case many. Apparently the plywood base, only two years old but poorly built, gave way beneath the sculpture, a putative masterwork of the transition between medieval and renaissance understandings of the figure.

This time, no seductive rib-girl precipitated the Fall of Man, just bad carpentry. He crashed to the ground unheard, to be discovered later by a guard on his rounds. The Met puts a brave face on for the Times – Philippe de M. himself promising so flawless a restoration of Adam that “only the cognoscenti will know.”

You recall the sculpture well, passed it dozens of times, but are certain that the figure possessed a navel. So how could he have been Adam? Or was there an Adam before Adam? In which case this Adam may not be all he’s cracked up to be. Perhaps they’ll restore the statue sans nombril – more authentic that way.

I think, therefore I’m Adam.

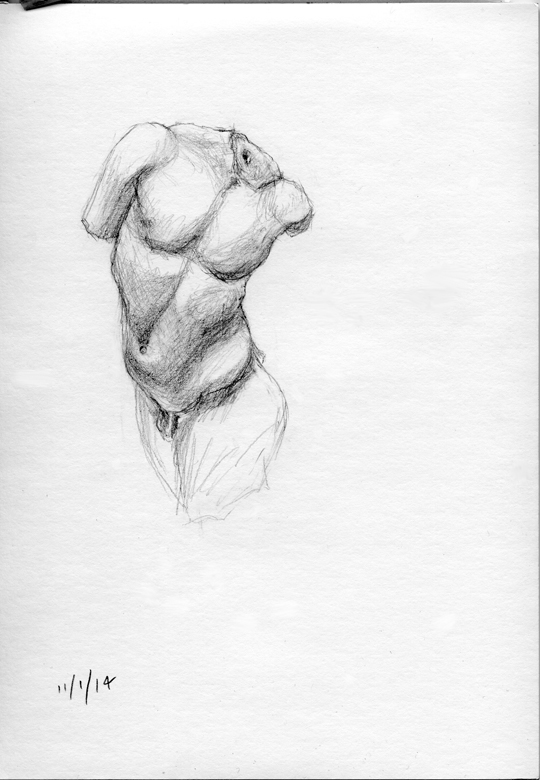

And walking through the still Adam-less Patio, on November 7, 2014, writing this the next morning, you’re not so sure you didn’t dream him.

I think, therefore I’m mad.

With the arrival of Jean-Baptiste Clésinger’s La Bacchante in 1848 – his similarly posed Femme Piquée Par Un Serpent had been the succès de scandale of the previous year’s Salon – illusionistic art reached its point of saturation: a moment when even the disciples of Dionysius had succumbed to an Apollonian conversion by metamorphosis. And this even as workers and students made the Communist Manifesto manifest in streets by the tens of thousands, and, in the Great West, three in every four San Franciscans abandoned their city in search of auric glimmers up the creek in Sutter’s Mill.

It was alleged that Clésenger had cheated, that he had used a body cast to render so lifelike a figure, even unto the lovesome dimples on Apollonie Sabatier’s thigh. “A daguerreotype in sculpture,” wrote Delacroix in his journal. But such attacks missed the point. The game that had begun with Galatea now came full circle, closing off its line for further development. Extreme determination had effectively separated concrete form from the spirit dimension. But not content to lie down and die, Western art heroically attempted to wrench itself onto another plane. “By deforming form, that is, by working against its submission to realism, by emancipating itself from any objective reference and making it ‘abstract,’ European painting [and sculpture] detaches form, promotes it, and spiritualizes it. Cézanne breathes life into his Bathers through the ascending motion of the triangle. According to Wassily Kandinsky, ‘the more organic form is pushed to the background, the more abstraction moves to the foreground’ and gains spiritual resonance.” [Jullien, The Great Image… p. 88]

But what is gained, and what is lost in such a desperate move? Can body and spirit really be split?

“You don’t paint souls,” said Cézanne, “You paint bodies: and when bodies are well painted, shit!, the soul, if they have any, the soul radiates and shines through from all sides.” [Joachim Gasquet, Cézanne, new ed., Paris: Cynara, 1988, p. 164]

The culture’s propensities mediate those of the individual.

Infinite onion.

November 9, 2014

And then, as though by virtue of some diurnal respiration, the Met announces, via the Times, our Adam’s imminent return.

With head attached, Adam tops out at six foot three.

While Kindness, Simplicity, Charity and Sobriety barely reach his forearm’s length – even with their arms upraised to support the dolphin dome from which trickles the life-giving, earth-sustaining water. Caryatid sisterhood of the myriad public fountains of Paris, sculpted by Lebourg and named for their donor, Richard Wallace, the Francophile English Baronet who also loved La Présidente.

We shall have recourse to return here too, to take refreshment from the inexhaustible fount of forms, of spirit dimensions and their lodgings, even to the Fountain of Innocents in the First Arrondissement, that once, upstream in the flow of language, was known as La fontaine des nymphes.

Sister Writer:

Baldwin extended the line of “love,” the West’s epic and heroic invention for suturing the great split it invoked in antiquity, to its maximum extent. In so doing, he became the pine tree on the mountain: a symbol that showed, as in a hanging scroll, the lay of the land.

Yet once again, the act stood in for the process, the message was reduced to a man.

But Baldwin’s work, particularly his long fictions, is permeated by a prolonged close encounter, and occasional merging, of body and spirit, and in certain passages, particularly when he speaks about breathing – as in his last novel, Just Above My Head, p. 216, and in the dream at the end of that book – he verges on a unitary mode that folds “love” into the One, that joins writing with the great alteration: winter, summer, day, night, inhalation and exhalation. It is in these traces that he suggests, however unconsciously, the foundational structure of a practice and a path that, ultimately, eluded him. But we remain.

Crunch lay as he had left him. One arm was at his side, one arm lay stretched where Arthur had been. His breathing was slow and deep – yet Arthur sensed that Crunch was not entirely lost in sleep. Arthur crawled back into bed, pulling the covers back up. The moment he crawled into bed, Crunch, still sleeping pulled Arthur into his arms.

And yet, Crunch lay as one helpless. Arthur was incited by this helplessness, the willing helplessness of the body in his arms. He kissed Crunch, who moaned, but did not stir. He ran his hands up and down the long body. He seemed to discover the mystery of geography, of space and time, the lightning flash of tension between one – moment? – one breath and the next breath. The breathing in – the breathing out. The miracle of air entering, and the chest rose: the miracle of air transformed into the miracle of breath, coming out, into your face, mixed with Pepsi-Cola, hamburgers, mustard, whatever was in the bowels: and the chest fell. He lay there in this urgency for a while, terrified, and happy.

Just Above My Head, p. 216.

Verbs: to abstract, to obstruct.

Nouns: obstruction, abstraction.

Why do your children keep getting in the way of my bombs?

From Hall Montana’s dream, Just Above My Head, p. 596:

Then, everyone is laughing. I have made a fire. We have fed the children, and the children are in bed. We are all drenched from the rain, even though I don’t remember that we ever left the porch. The fire begins to dry us, at the same time that it makes us know how wet we are. And Arthur repeats his question.

“Shall we tell them? What’s up the road?”

In Daoist practice the basis of qi – that which animates life and generates forms – is the intertransformation of water (kidneys) and fire (heart). This is hardly the only allusion in Baldwin’s texts to the dynamic interplay among these elements, referred to in Daoist literature on breathing, meditation and physiology, as “internal alchemy.” It is believed that the regulation of the breath in meditation facilitates the generative, and life-sustaining process of this cycling between “opposing” elements, which, in Chinese cosmology are not in separate, but reciprocal.

Thus the solid inner yang line between two broken yin lines in the element water, shows its hidden fire, as the inner yin line within the solid top and bottom lines of the fire trigram signifies its hidden water.

The elemental reference in the title of Baldwin’s essay collection The Fire Next Time (1963) is sharpened further by the book’s epigraph. Drawn from a negro spiritual, the epigraph poses a dyadic and imperative either-or – the classic Western zero-sum game: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, / No more water, the fire next time!

Which, for Baldwin, is a warning about disintegration, i.e. the failure of intertransformation. Water, fire, black, white: these are not “pure,” and therefore mutually exclusive essences for the Daoists, or for Baldwin. They are, as the tai ji indicates in graphic terms, inextricably bound together. Yet, as he said to an interviewer around the time that Fire… was published: “As long as you think you’re white, I’m forced to think I’m black.”

Satyr turning to look at his tail.