XXXV

Spirito con carne.

It is lion-headed Phobos who mediates between Thanatos and Eros. How we process fear has everything to do with whether we default toward death or toward the generative principle.

Going to Mediate the Man.

What price must the word pay to be effective?

Present indicative, mon amour.

What quality is the gaze?

And what looks back at you?

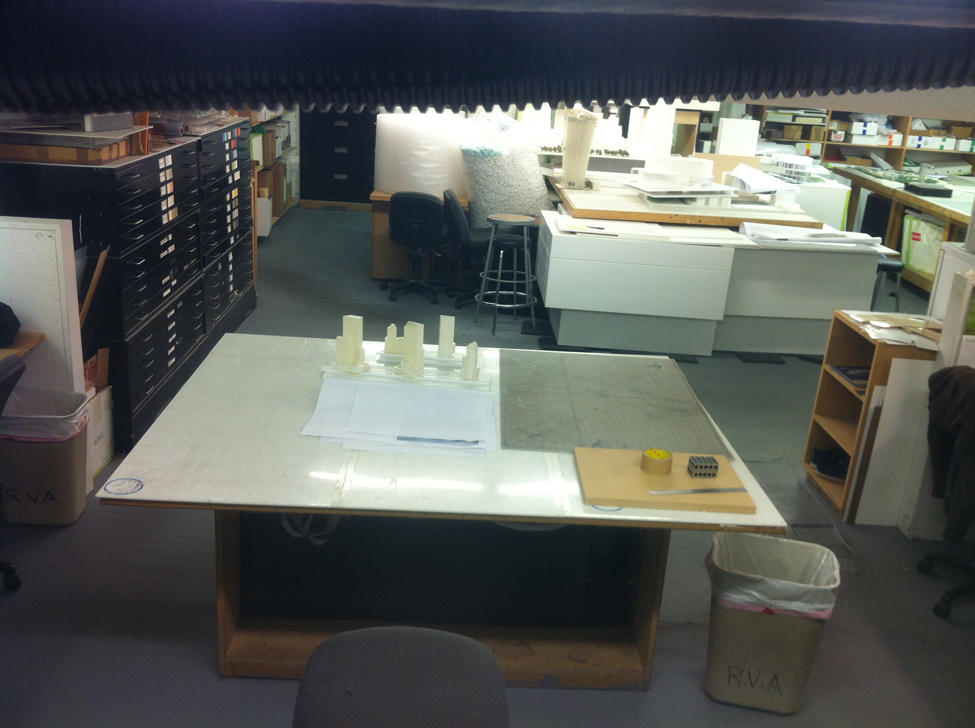

And what of the day, dolce far niente, when the drive to make a Freedom Tower transmutes into a natural, easy, so much more grounded freedom-from-having-to-make-towers?

Uncomfortable, but necessary to acknowledge, that literacy, literature, and the culture of books can prove a wondrously effective means of promulgating ignorance. And of placing knowledge at a remove from the knower.

In the West, there is a tendency for symbolic value to dominate all other forms of value. And to become something inherently “out there.” Is this a consequence of alphabetism?

Are we trying to get out of the alphabetic trap by collapsing language – both written and spoken – into a zone of no meaning? They call it texting, this depleted utterance that is all sorts of things, but not a text. Or, in branded form, tweeting. Though that term greatly misestimates the efficacy of bird calls in fostering their propagation and survival.

To what degree is to say to do – or in certain languages make? Can saying and doing/making be coextensive? Are they possibly discrete? Overlapping? Continuous? What is the relation of the symbol to the concrete thing?

Authenticity mon amour. And the discontentedness of its discontinents.

Leiber (of Baltimore) and Butler (a Brooklyn lad and graduate of Erasmus Hall High) wrote the song in the Brill Building on Tin Pan Alley.

Alvin Robinson had a hit with it first, in ’64, then later, the Stones and the Coasters did too. It’s rude, it’s crude, but what does it say?

Lord I swear the perfume you wear

Was made out of turnip greens

And every time I kiss you girl

It tastes like pork and beans

Even though you’re wearin’ them

Citified high heels

I can tell by your giant step

You been walkin’ through the cotton fields

Oh, you’re so down home girl

Tryin’ to make it real. But compared to what?

“My text, this morning,” Julia said, “comes from the Psalms of David. Please turn, with me, to the Thirty-first Psalm, and we will all read together the twenty-first verse.”

She was dressed all in white, and standing on a platform which was hidden by the pulpit. This was a special, collapsible platform, constructed by her father, and she looked at him as she stood there, and as he stood up to read. The hidden platform looked like a wooden box, with a rope handle. When her father opened it, with his boyish flourish, the box became a platform with one short step, and the rope handle became a handrail, sometimes painted gold. This contraption, and her father, traveled with Julia everywhere: and made Julia’s appearance in the pulpit seem mystical, as though she were being lifted up.

Her mother and father were before her, in the front row, with Jimmy restless between them. They hadn’t long arrived from New Orleans, and our mother and father had known Julia’s grandmother. We sat right behind them, our mother and father, and Arthur and me, on a Sunday morning. It was weird to have been dragged to this church to hear a child, who was nine years old, preach the Gospel. Somebody was jiving the public, and I knew it had to be her father and mother, who surely did not look holy to me.

Julia’s mother put up a better show, though her hats were flaunting, and her skirts were tight. She had one beautiful ass, and high, tight, demanding breasts, and long legs, and she always wore high heels – just to make sure you didn’t miss those legs. When she got happy, she would stroke her breasts, and I would watch her thighs and her legs and that ass of hers as she started to shout, and I would get such a hopeless, unregenerate, eighteen-year-old hardon in the holy place that you could certainly hear this sinner moan.

Her father made very little pretense – he didn’t have to, being her father. He was the zoot-suited stud of studs – a mild zoot suit, driving ladies wild wondering what he’d be like wild. He had the cruel, pearly teeth, and the short, black, tickling mustache, and tha grin of the sinner man just waiting for the touch that would bring him salvation, and thick, curly, good black hair. His eyes were like Mexican eyes, and he seemed, in all things, indolent, waiting for you to come to him.

I was not the only one who would see all this change, but, at that time, Brother Miller had the world in a jug and the stopper in his lean brown hand.

The church was packed, for a child evangelist was, after all, something in the nature of a holy freak-show, and also something more than that, something which spoke of the promise and the promise fulfilled. And this child came from the Deep South, which we, the children, had never seen but which our parents remembered, with yearning and fear and pain.

She was a small child, darker than her father, with hair coarser than his, hair now mainly covered by the crocheted holy cap. Her father’s eyes were very bright. Her eyes were dark, flashing, and seemed unbelievably ancient in the tiny, untouched face. Arthur said she was a witch, and could put a spell on you, or else she was a dwarf about a hundred years old, and Brother and Sister Miller had stolen her from Egypt.

She did not sound like a child as she read, and we read behind her – and I still remember feeling very strange, as though I were making, simply by the sound of my voice, some relentless, mysteriously dangerous vow:

“Blessed be the Lord,” we read, “for he has shown me his marvelous kindness in a strong city.”

From James Baldwin, Just Above My Head, a novel, 1979, pp. 65-67.

Every time you monkey child

You take my breath away

And every time you move like that

I gotta get down and pray

Don’t you know that dress of yours

Was made out of fiberglass

And every time you move like that

I gotta go to Sunday mass

Oh, you’re so down home girl

If one wishes to be instructed – not that anyone does – concerning the treacherous role that memory plays in a human life, consider how relentlessly the water of memory refuses to break, how it impedes that journey into the air of time. Time: the whisper beneath the word is death. With this unanswerable weight hanging heavier and heavier over one’s head, the vision becomes cloudy, nothing is what it seems. The word, event, has no meaning, except in a ritual sense: in the sense, that is, of a vow, a bowing low between the earth of the future and the sky of the past: with joy. You cannot see when you look back: too dark behind me. And the song says, merely, with a stunning matter-of-factness, “There’s a light before me. I’m on my way.”

How then, can I trust my memory concerning that particular Sunday afternoon? Memory does not serve me, I had nothing to remember then. Julia was a nine-year-old girl; I was eighteen. I did not know that she would leave the pulpit, turn into a whore, and then, the mistress of an African chief, in Abidjan. I did not know that we would become lovers, and that she would become one of the pillars holding up my life. I knew nothing about Arthur, who was then eleven, and less about Jimmy, who was then seven, who would become Arthur’s last and most devoted lover. Who could know that then? Beneath the face of anyone you ever loved for true – anyone you love, you will always love, love is not at the mercy of time and it does not recognize death, they are strangers to each other – beneath the face of the beloved, however ancient, ruined and scarred, is the face of the baby your love once was, and will always be for you. Love serves then, if memory doesn’t, and passion, apart from its tense relation to agony, labors beneath the shadow of death. Passion is terrifying, it can rock you, change you, bring your head under, as when a wind rises from the bottom of the sea, and you’re out there in the craft of your morality, alone.

Just Above My Head, p. 71.

I’m gonna take you to the muddy river

And push you in

Just to watch the water roll on

Down your velvet skin

I can be fairly sure of some things. I was eighteen, thirty years ago. The country was between wars, and nobody had quite got his shit together, the killing shit, though everybody was heading in that direction. The pause was useful. Paul [the narrator’s father] played piano in a joint uptown, in what had been Sugar Hill. Mama had a family in the Bronx, and they loved her. I had a job in the garment center but not pushing a wagon, thank you, I was a shipping clerk… I was going to night school, we were hoping to send Arthur to college.

If I was going to night school, then we were living on 135th Street, between Fifth and Lenox. I remember the subway ride. We were worried because we heard they were going to tear down our building to make room for a housing project.

I remember that we walked from church, because Jimmy had a tantrum, wanting to pee. His mother was terribly embarrassed, but his father laughed and stood beside him while Jimmy peed between two parked cars.

“You feel more like a man now?” his father asked; and Jimmy turned away, and buttoned up. For a moment, I had the feeling that he was about to run across the street and get himself killed. But he took is father’s hand and walked beside him.

Just Above My Head, p. 72.

I’m gonna take you back to New Orleans

Down in Dixieland

I’m gonna watch you do the second line

With an umbrella in your hand

Oh, you’re so down home girl

We got to the house and climbed the three flights of stairs, Arthur running ahead of us to unlock the door… My parents climbed the stairs behind me… and I was behind… Julia and Jimmy. The children’s mood had changed.

“You a story!” Jimmy whispered, fiercely, to his sister. This was on the landing. Their parents had started climbing the third and last flight of stairs; and I had the feeling that they too, like my parents behind me, were resting for a moment.

“I’m in the Lord’s hands,” Julia said calmly.

But she stumbled as she started up the third flight.

Jimmy said with a venom which almost made me stumble:

“You lucky you ain’t in mine!”

And Jimmy looked at his sister with hatred, as though he wished to push her down the steps, or hurl her over the railing. We all go to the top of the steps, and entered through the open door.

Arthur had opened the wrong door, that is, he had opened the door which opened on the small room which led to the kitchen and the bathroom instead of the door which opened on the living room: and the silence was a little heavy as we walked through the two dark bedrooms which led to the front of the apartment. I head during that passage, “Now Jimmy, you be good, you hear me?” and his mother slapped him, hard, twice, across the face. Jimmy didn’t make a sound. He ran head of my parents and me, into the living room, and stood at the window looking out.

“Well. Make yourselves at home,” Paul said, smiling, and not knowing what else to say, and staring at Jimmy’s back.

Florence [the narrator’s mother] glanced at Amy [Julia and Jimmy’s mother] briefly, as though she were seeing the past and the future, as though, as though there were something she wanted to tell her – or perhaps as though she wanted to strike her – and Amy sat down on the sofa, beside her husband. She didn’t look sexy to me now, she didn’t even look pretty. She looked like a skinny, scared young thing, not bright, not nice at all. And the dude beside her was suddenly just that, a dude, and he looked frightened, shrunk all inward, as though he were in the hands of cops in the precinct basement and about to inform on his mother.

It was a kind of frozen moment. Florence walked out of the room. Julia ran and put her head in her father’s lap. But both these moments seemed frozen. Arthur moved toward Jimmy, slow and shy, and Paul said, “Hall, take them on down to the ice cream parlor. Dinner won’t be ready for a few minutes.”

So I was the one who grabbed Jimmy around the neck and pulled him out of the room, and Arthur followed us. We got out of the apartment and Jimmy started to cry and I sat down on the steps and I held him and Arthur stood there. An awful lot began that day, looing back; I know that a lot of what happened could not have happened, had it not been for that day; and yet, Jimmy hardly remembers it at all. He remembers, and not at all the way I do, that his father let him piss between two parked cars [on the way home from church]: and I guess that makes sense too. Lord. Did you say something about being wonderfully and fearfully made?

I walked my two charges around the block, very much the big brother now, and digging it, and, though I knew it might spoil their appetites, bought them ice cream sodas and sat at the counter smoking a cigarette and bullshitting the girl behind the counter. I must say that I loved my brother, Arthur, very much that day because he was being very nice, not forced-and-phony nice but really nice. He was hurt that this snot-nosed kid he’d been snubbing, had been hurt and was doing all he could to make amends – and had the grace not to seem to be making amends, not to have noticed that anything had gone wrong. He got Jimmy to laugh. I was to forget all this later, but then, later, it was all to come back to me. When I thought they’d laughed enough over secrets they would never entrust to an old man like me, I stood them up and paid the bill and walked them back around the block, to the house. I carried Jimmy piggyback up the stairs and Arthur ran up the stairs ahead of us, like the advance patrol.

“Why,” Amy was saying, as we entered the living room, “when Julia was called – “

“How old was she?” asked Florence.

“I was seven,” Julia said. She was sitting on her father’s lap, motionless, using him the way the Sphinx uses the plains of Egypt.

Just Above My Head, pp. 73-75.

Regardless of the atmosphere, the moms or dads walking their kids toward school, particularly the ones holding the hand of a child in each hand, look as though they are moving into a powerful headwind. One almost feels their ears pinned to the sides of their heads, eyes streaming behind.

Reality: freely available to all.

We skipped a life, and dangled;

Terns, scarred, reeled costa flor…

And latent mounds of green.

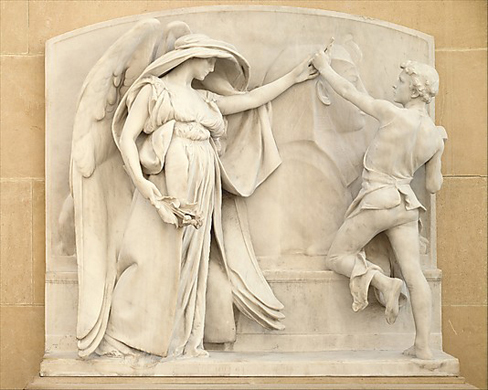

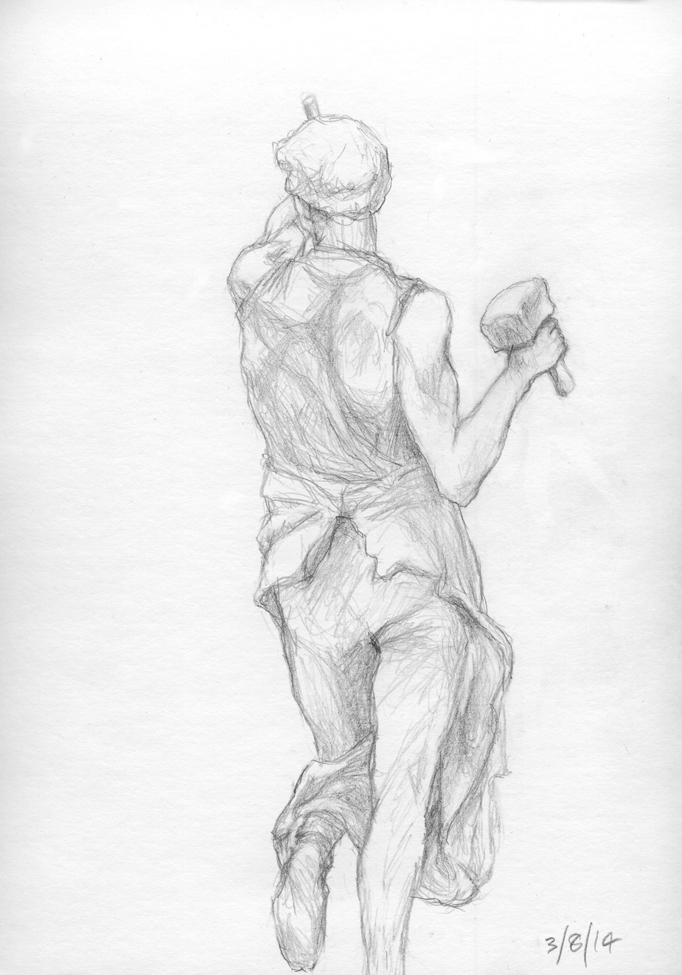

In the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum is striking piece of statuary called “The Angel of Death and the Sculptor.” Both angel and sculptor are, more or less, life sized and how they came to their present position in the sculpture court adjacent to a cafeteria is a curious tale, which, for our purposes begins with the death of Boston sculptor Martin Milmore in 1883 at the age of 39. When his brother Joseph died three years later, their family commissioned Daniel Chester French (1850–1931) for a bronze funerary monument to be erected at the Milmore plot in the cemetery at Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts. In 1893, a year after the massive bronze was installed at the gravesite, French exhibited his plaster model at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where it received acclaim sufficient to catapult the sculptor, already ascendant, into the highest ranks of his profession and eventually to a trusteeship at the Met.

In 1917, the Met’s president, Robert W. de Forest – a protégé of robber baron Russell Sage and later head of the Regional Plan Association, a body composed of New York’s financiers, rail men and major land owners – asked French to cast a bronze copy to grace the ever-expanding yet not quite “arrived” Museum. French – well understanding the codes of parvenu Classicism – replied, in essence, “go with marble, it’ll knock their socks off,” and entrusted the work to the city’s then-premiere marble carvers, Piccirilli Brothers, who, among other commissions, rendered French’s vast Honest Abe for the DC memorial, Atillo Piccirilli’s Maine Monument in Columbus Circle and Henry Clark Potter’s New York Public Library Lions.

And this is how you came by the image below, sculptor interrumpitur,

sitting in the Met cafeteria on the first springish day of 2014, snow still whitish on the ground visible through the glass window wall to your right, and French’s figures at the perfect angle to your left, buzz of voices all around.

“Tomorrow I must see you – somewhere where we can be alone,” he said, in a voice that sounded almost angry to his own ears.

She wavered, and moved toward the carriage.

“But I shall be at Granny’s – for the present that is,” she added, as if conscious that her change of plans required some explanation.

“Somewhere where we can be alone,” he insisted.

She gave a faint laugh that grated on him.

“In New York? But there are no churches… no monuments.”

“There’s the Art Museum – in the Park,” he explained, as she looked puzzled. “At half-past two. I shall be at the door…”

She turned away without answering and got quickly into the carriage. As it drove off she leaned forward, and he thought she waved her hand in the obscurity. He stared after her in a turmoil of contradictory feelings. It seemed to him that he had been speaking not to the woman he loved but to another, a woman he was indebted to for pleasures already wearied of: it was hateful to find himself the prisoner of this hackneyed vocabulary.

“She’ll come!” he said to himself, almost contemptuously.

Avoiding the popular “Wolfe collection,” whose anecdotic canvases filled one of the main galleries of the queer wilderness of cast-iron and encaustic tiles known as the Metropolitan Museum, they had wandered down a passage to the room where the “Cesnola antiquities” mouldered in unvisited loneliness.

They had this melancholy retreat to themselves, and seated on the divan enclosing the central steam-radiator, they were staring silently at the glass cabinets mounted in ebonised wood which contained the recovered fragments of Ilium.

“It’s odd,” Madame Olenska said, “I never came here before.”

“Ah, well –. Some day, I suppose, it will be a great Museum.”

“Yes,” she assented absently.

She stood up and wandered across the room. Archer, remaining seated, watched the light movements of her figure, so girlish even under its heavy furs, the cleverly planted heron wing in her fur cap, and the way a dark curl lay like a flattened vine spiral on each cheek above the ear. His mind, as always when they first met, was wholly absorbed in the delicious details that made her herself and no other. Presently he rose and approached the case before which she stood. Its glass shelves were crowded with small broken objects – hardly recognizable domestic utensils, ornaments and personal trifles – made of glass, of clay, of discolored bronze and other timeblurred substances.

“It seems cruel,” she said, “that after a while nothing matters… any more than these little things, that used to be necessary and important to forgotten people, and now have to be guessed at under a magnifying glass and labeled: ‘Use unknown.’”

“Yes; but meanwhile –“

“Ah, meanwhile –“

As she stood there, in her long sealskin coat, her hands thrust in a small round muff, her veil drawn down like a transparent mask to the tip of her nose, and the bunch of violets he had brought her stirring with her quickly-taken breath, it seemed incredible that this pure harmony of line and color should ever suffer the stupid law of change.

“Meanwhile everything matters – that concerns you,” he said.

She looked at him thoughtfully, and turned back to the divan. He sat down beside her and waited; but suddenly he heard a step echoing far off down the empty rooms, and felt the pressure of the minutes.

“What is it you wanted to tell me?” she asked, as if she had received the same warning.

Edith Wharton, wrote that, recalling on the eve of the Roaring ‘20s, the Age of Innocence some forty years past.

The latest and degradest.

Radical usage.

Does innocence carry an aegis, or come under one?

Hillel Manger, was a master tailor for whom literature constituted a sacred practice: “literatoyreh”: literature + Torah. A tailor would, of course, have an affinity for portmanteaux.

His son Itzik, an incandescent spirit – part prophet, part trickster – referred to himself as a “master tailor” of the written word. His retellings of the Bible, adding characters, giving voice to speechless characters and silencing more powerful ones, have generally been interpreted as iconoclastic, and his project seen as one of deserialization, albeit more mischievous than blasphemous. But perhaps it was – or was also – an oblique strategy for rescuing, for revitalizing, the spiritual content of texts endangered by the frozen energy of their canonic status?

The selfie of Dorian Gray.

Quarter-inch marble.

I walked to the Village on that freezing night, on which I felt, just the same, so warm. It wasn’t late yet, not quite ten, and all the stores stayed open late tonight, honoring the birthday of the Prince of Peace. And, I suppose, if I really want to get down about it, that they really were – out of the same, blind, self-seeking wonder that forced them to crucify Him. Well. I don’t really want to get that down about it: them is always us, they are always we. With that and a subway token, you can ride from here to glory. A long ride, pilgrim, stopping at doom, despair, confusion, and loss, with a change of trains at Gaza: at the mill, with slaves.

Which is some of what Hall Montana tells in Just Above My Head.

New masters for old!

Selfie as other.

One potentially quite bracing revelation characterizes our moment: the cabal of men, and women, brutes and bullies, and their myriad colluders and enablers, is not merely bent on destroying the lives and dignity of their fellow human beings. They are intent on annihilating the planet itself. Nothing less than that will constitute the achievement of their goal. It is a strange turn on Oedipus. If you can’t fuck mother, or are knotted up with guilt because you did, then the only way out is to kill her. Et tu, Boo Boo?

When the day comes and cartoons speak for themselves:

Yogi, is it possible to have freedom without dignity? And if you could only have one, which would you choose?

Whoa, Boo Boo – those are some very interesting questions…

Property: the obverse of dignity.

One gaze fits all.

LET US SING SIMPLY

Let us sing simply, directly, and plain

Of all that’s familiar and dear.

Of agéd beggars who curse at the frost

And of mothers blessing the fire.

Of indigent brides with their candles who stand

At sightless mirrors, forlorn,

Each of them seeking the intimate face

They loved and that laughed them to scorn.

Of those who cast lots and who steal the last coin

Of their victims with speech that’s obscure;

And of wives who, deserted, curse at the world,

Slinking away through back doors.

Of housemaids whose fingers are worked to the bone

And who hide from their mistress’s sight

The morsels they save for the soldiers who cone

One their visits to them every night.

Let us sing simply, directly and plain

Of all that’s familiar and dear.

Of indigent mothers who curse at the frost

And of beggars blessing the fire.

Of young women in summer forced to abandon

Their bastards on doorsteps, and quail

At the sight of the man in a uniform

Who is able to send them to jail.

Of the hurdy-gurdies that grind and grind

In poor courtyards on Fridays all day,

And of thieves surprised at their work who must

Flee over the rooftops away.

Of ragpickers picking their way through debris,

Who dream of the treasure they’ll find,

Of poets who foolishly trusted the stars

Them promptly went out of their minds.

Let us sing simply, directly, and plain

Of all that’s familiar and dear.

Of agéd folk who curse the frost

And of children blessing the fire.

So sang Itzik Manger, translated by Leonard Wolf.

A bibliography:

Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1997.

The World According to Itzik: Selected Poetry and Prose by Itzik Manger, edited and translated by Leonard Wolf. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Art and Myth in Ancient Greece by Thomas H. Carpenter. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991.

Song the gaze.