XCV

Truth is a leaky bucket

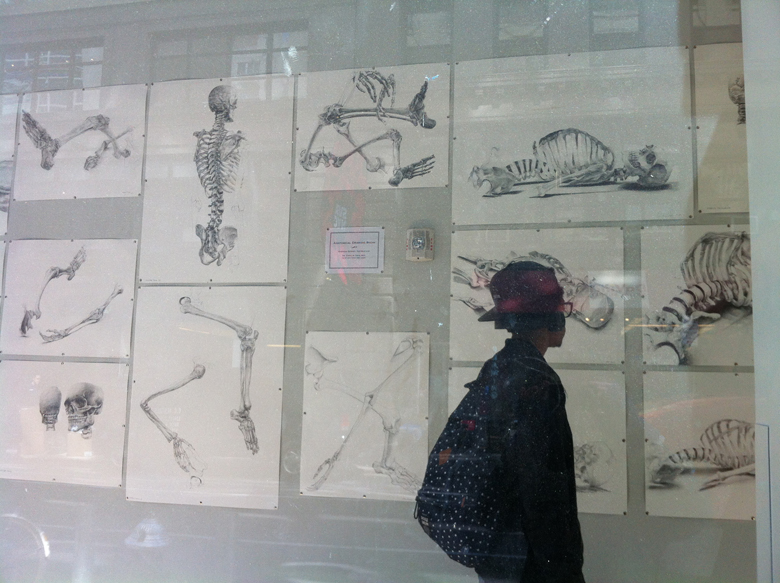

The sun dominates, the heavenly vault covers, and the ground below gives nourishment: it could be said that the entire system of the universe is to be found within the form of the nude – it is form itself; here the universe breathes as it does in the recurrent movement of waves.

So says Jullien […Nude, pp. 110-111], then immediately backs into a familiar corner: the grand opposition – rather than the taiji of East and West. After several tortured sentences, he proclaims: “With its whole body stretched taut to cover the invisible, as though it alone, yet in its entirety, were the visible side of another world, the form of the nude signals other demarcations. Raised on a pedestal by an entire civilization, it shows a glimpse of other splits in its foundations. In particular, it points to the interest that first Greek and then European culture showed in modelization…”

Yes, François, we got it the first time, the second time and the hundredth. The question remains: why allow Western ontology to define the nude, if another path – one might say a dao – is available – one which has no dog in the fight of another plane, but which accepts the compenetrability of visible and invisible realms: a view of the whole which, as the saying goes, has “no skin in the game”?

But he goes on to distill a key distinction – key in that it opens up the logic of distinct approaches to describing reality. “Chinese civilization,” he says, “is mistrustful of the revelatory power of the image… it prefers to schematize indices such as the cracks that appear on bones or tortoise shells subjected to flames. [Or the wrist pulses, tongue colors and textures that form a basis for Chinese medical diagnosis.] It seems to me that Chinese ‘reason’ is less modelizing than schematizing…”

With reference to Chinese strategies of depiction, he notes that “Chinese illustrations [in the Mustard Seed Garden Manual] schematize both the ‘attitude’ and the ‘intentionality’ (du and yi) much as ideograms do… for what is rendered is not the cleverly analysed movements of physical strength, but a movement of inner tension, captured in a ‘cursive’ line that expresses what is happening with the figures between them. Their intentionality is apprehended ‘from afar,’ preserving the ability for further development…” […Nude, p. 115]

Following this logic, why, in drawing the figure, need one build on a layer of fabric, or folds, movements of sleeves, etc.? Cannot the “literal” fact of the nude body retain its allusive qualities? Can it not claim the depth of its intentionality clothed in the “web” of its skin. Cannot the artist make herself available to the shared breath intention of which that “other” body is yet another mutable and mutating form?

Build as little as possible

Nobody’s white if everybody’s Wong

Survivor’s guild

A naturally occurring person

And if you’re taken by

the spirit of your age

no reason to carve a cornerstone

sang Bryan Ferry oncet

Who is this Phil?

And why is he trying to ossify?

Big boss man

Don’t you hear me when I call?

Big boss man

Don’t you hear me when I call?

Well, you ain’t so big

You just tall, that’s all…

Think outside the Bachs.

Said Mozart.

(Baroque joke, said someone else)

Three rubber chickens, one Kosher, one Halal and one Born Again, walk into a bar…

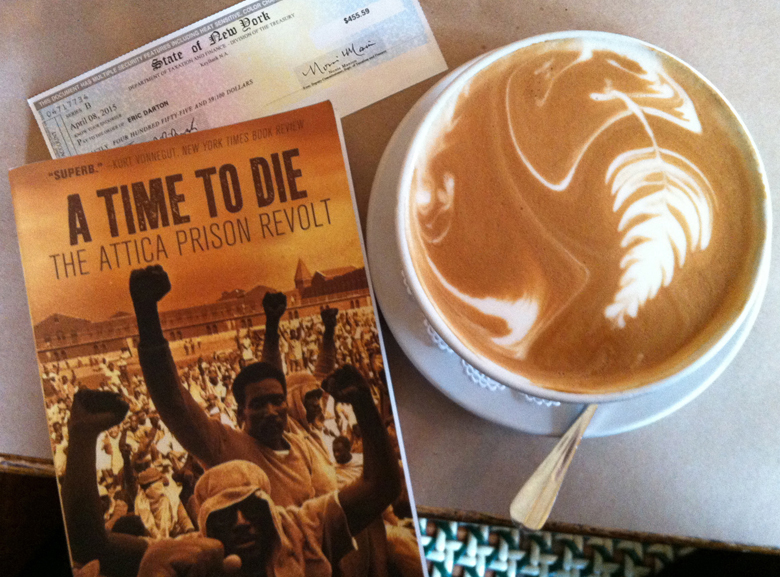

Not far from Cell 15, Wicker was speared by an impassioned speech demanding that those in C-block be allowed to join “the brothers in D.” Wicker tried to explain that the prison authorities wanted to put an end to the revolt and were hardly likely to let more rebels into D-yard. This reasoning made no impression; he was face to face with one of the most peculiar aspects of the Attica uprising. Many of its participants and supporters regarded it less as a power play or an unexpected opportunity (or danger) or even a political act (whether in the cause of prison reform, black power, or social revolution) than as a proper condition in itself, of greater validity than the restoration of accustomed authority.

This was manifested, for example, by inmate outrage at the notion that the administration might attempt to “starve out” the men in D-yard. Many inmates seemed to think it was the administration’s duty to sustain the revolt – by food, water, medical care, etc. – rather than to end it. And the C-block prisoner [Wicker had spoken with] seemed to think he had a “right” to join men who also had a “right” to hold D-yard.

Wicker never quite adopted that attitude as some of the other observers did. He could see a possible need for the uprising as a protest against conditions, but that was only to say that the state should improve the conditions – which he wholeheartedly believed. Wicker’s instinctive, conditioned, middle-class loyalty ran to the state and its institutions, even when his sympathy ran to their victims, because he had a strong belief in the good intentions of the state, which he tended to confuse with its people…

In another cell, an overflowing toilet brought an unpleasant phrase out of Wicker’s memory – some stricture he could not quite recall on a man who would “shit where the eats.” To be forced to shit where he slept, at the head of his bed as it were, was an indignity Wicker resented for the meanest inmate – yet, even as he thought it, he knew that if the idea of prison was accepted at all it required such toilet arrangements. You could hardly have the inmates in and out of their cells, back and forth to the urinal, at will. He was seeing more specifically… that the idea of prison was wrong. [Wicker, A Time to Die. pp. 63-64]

Why?

Some six hundred years before the Great Society was a reformist twinkle in LBJ’s eye, another Great Society was thought to be, and very possibly was, the organization behind the Peasants Revolt of 1381. Though the Revolt, also known as Wat Tyler’s Rebellion, or the Great Rising was suppressed by the crown and nobility with all-too imaginable violence, the words attributed to one of its leaders, the Lollard preacher John Ball, and representing, presumably, the sentiments of the insurgents, ring on with undiminished sonority:

We are men formed in Christ’s likeness, and we are kept like beasts.

When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?

Therefore: All things under heaven ought to be common.

Don’t jump to illusions

Brothers:

The situation in C-block is thus: We are lock in, we have requested to be let out in the yard, but that’s out. The water situation is very dim, they say a main is busted – I think not! But we have been getten water from the Brothers, from the windows and from the pig, when ever he feels like giving us some.

Brothers please don’t give! This is new for them and they don’t know how to react!

We are ok.

Hold on as long as you can

Big Black

Bro. Herb

Bro. Richie

Carlos

and all of you

Right On!

[signed] Husey/ or Toby

(I’ve just heard the news on the phones, you are looking very good, keep it together)

[Handwritten note surreptitiously passed to Tom Wicker, September 10, 1971, by a C-block prisoner to be given to Frank “Big Black” Smith in D-yard. Wicker and other observers had been asked by the D-yard rebels, and allowed by the administration, to check into allegations that the prisoners in C-block had been tear gassed and beaten by guards. From Wicker, A Time to Die. pp. 65-66]

Have your frivolous suits call my frivolous suits

In a fierce dinner-table debate with James Baldwin, Tom Wicker had once declared a willingness to trade his white skin for Baldwin’s literary talent. If obviously futile, this proposal reflected a genuine frustration and a searing ambition. He had always wanted to be a writer, and had become one, but not as he had anticipated. [Wicker, A Time To Die, p. 19]

Propose alteration of NYC nickname to Gol’gotham.

And the establishment of a Committee for More Accurate Urban Nomenclature. On the agenda for Session One the CMAUN will consider changing:

The United Nations to Rockefeller Center 2

Lincoln Center to Rockefeller Center 3

World Trade Center to Rockefeller Center 4

Riverside Church to Rockefeller Center .5

The Cloisters to Rockefeller Center .75

Or voids to that defect

Agincourt. Evening around the campfire. Power people! We are strong. We are together. We are growing. We love you all. Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh. Please inform our next of kin.

So wrote Sam Melville (né Samuel Grossman), September 10, 1971, in a note brought out of D-yard by an observer. [Wicker, ATTD, p. 74]

Attica: a classic case of stuck, stagnant, pathogenic qi.

I hope we will have enough bread by the time D.M. comes out to California with the cats to pay for their flight.

Sam got 15 years. Dave [Huey] 60 days psychiatric observation at Bellevue. Wouldn’t be surprised if he is permanently committed. Numerous bombings and attempts in the area. More shit coming down in Northern Ireland. Miami and Isla Vista are cooled, but it looks like the summer may be heavy. [Journal note, June 27, 1970, Berkeley, CA]

And in a Rabbie state o’ mind:

Can ye not feel it, man, the great web o’ texts?

CENSUS

On the hill where Troy once stood,

they’ve dug up seven cities.

Seven cities. Six too many

for a single epic.

What’s to be done with them? What?

Hexameters burst,

nonfictional bricks appear between the cracks,

ruined walls rise mutely as in silent films,

charred beams, broken chains,

bottomless pitchers drained dry,

fertility charms, olive pits,

and skulls as palpable as tomorrow’s moon.

Our stockpile of antiquity grows constantly,

it’s overflowing,

reckless squatters jostle for a place in history,

hordes of sword fodder,

Hector’s nameless extras, no less brave than he,

thousands upon thousands of singular faces,

each the first and last for all time,

in each a pair of inimitable eyes.

How easy it was to live not knowing this,

so sentimental, so spacious.

What should we give them? What do they need?

Some more or less unpeopled century?

Some small appreciation for their goldsmiths’ art?

We three billion judges

have problems of our own,

our own inarticulate rabble,

railroad stations, bleachers, protests and processions,

vast numbers of remote streets, floors and walls.

We pass each other once for all time in department stores

Shopping for a new pitcher.

Homer is working in the census bureau.

No one knows what he does in his spare time.

[Wisŧawa Szymborska, Poems: New and Collected. Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh, trans. New York: Harcourt, Inc., 1998]

Were she here, or I there I would say: Wisŧawa, Wisŧawa, lose those final stanzas – that’s where, like history, like story, you go wrong. They’re prisons only, that knot of last lines. Don’t try to tie it up, forget to clutch it to your bruised heart. Don’t build on Troy. Troy is as it is. It needs no irony, nor mourning.

And Helen, she was wherever the better, more impaled on the spear of perfect, her-his-or-its-story is made. And by being wherever the better story placed her, nowhere.

The most beautiful virgin, so the Greeks say, is ugly in comparison to a goddess.

Five virgins walk out of a reservoir…

Many thousands gone

In eighteen hundred and sixty-three

A Blinkin’ set the darkies free

And as for Paddy, poor Paddy…

His cordroy breeches he put on

For working on the railway:

underground, elevated, L’pool to Manchester, Highline…

Who is this A., and why’s he blinkin’?

And have you noticed that way that, given an Irish lilt, the word “poor” sounds like “pure,” and vice versa?

Saw a nude down at the corner of Good and Beautiful…