CLVII

Help! I’m trapped in a story and can’t get out!

Who shot John?

Nobody, man. He was stabbed.

Shanked?

Yeah, I guess you could say that…

Waiting for Lofty in Bryant Park near the paradoxically bronze Gertrude Stein. All around you on this fine day, young corporati sit on folding chairs eating takeout lunches at little round green tables. “Story over standards, dude,” crows one lad to his companion in a context you don’t catch, though it seems the punchline to a tale of sharp practice made perfect.

Story over standards.

Perhaps the motto of a generation.

Read it again

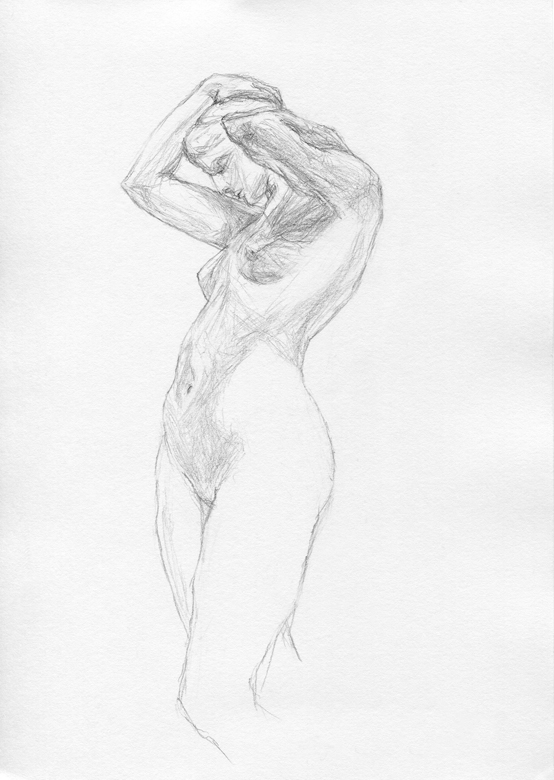

None of the fruits of ch’i dealt with representational knowledge, such as anatomy or perspective, but were truly the fruits of the spirit. Chang Yên-yüan referred to bone spirit (ku-ch’i), and Han Cho spoke of the structural essentials (t’i-yao) in contrast to terms used for the mere representation of form, such as form likeness (hsing-ssŭ) or formal resemblance (hsiang-hsing).

To the Chinese, trained to value the structural “ku” [bones] of brush strokes, our modeled plastic forms seemed blatant and vulgar: the T’ang men revolted against the Graeco-Indian “ideal” forms, and the Ch’ing painters called the Baroque paintings the work of unimportant artisans (chuang).

To them any good craftsman could make a fair copy of natural forms, but why call it art? Confronted by chiaroscuro and cast shadows, one Ch’ing critic tauntingly inquired whether Europeans were half white and half negro, since they painted faces with one side dark…

Even if these Chinese had seen paintings by Michelangelo instead of by Castiglione, the representational values would still have blinded them to the inner reality, just as we, until recently, have found it difficult to realize the structural truth to nature in a few Chinese brush strokes. [George Rowley, Principles of Chinese Painting, Princeton University Press, 1974. p. 37]

Capriccio with the Ruins of Washington Square Park and a Giant Tree Sloth

SIC: superficially in control

Shih [shi] has generally been translated reality in the sense that it is present when the artist comes to grips with reality. Originally it meant “seeds” and now is translated substance; therefore in critical writing, it has been contrasted with “embellishment” in the favorite literary opposition of fruit and flower – “fruit is the foundation, flower the outer extremities.”

None of these translations quite conveys the meaning of shih, which is the quality of having a life of its own. Aliveness or vitality might be used, if we keep in mind that the aliveness belongs to the work of art in its own right and not to the lifelike representation of any object in nature. Rembrandt, in his drawings, [and I would add etchings] had more shi than any other artist in the west, not because he imitated natural effects but because his pictorial forms, even of inanimate objects, were tremendously vitalized by a life of their own…

…This was the secret of the greatness of Giotto; his sacklike forms were corporeally unconvincing and his poses and gestures were frequently clumsy, yet his figures emanated a mysterious power, the presence of a spirit in flesh… This awareness of a presence should not be confused with the emotional situation. The shih can be hurt by too much expression of emotion as well as too much naturalism. Western so-called expressionists have been the chief offenders in this respect because they have exaggerated the emotional effect in the misguided hope that it would make their art more spiritual, and because in bad expressionistic art the artist has expressed his own emotions instead of allowing the images to carry their own message.

Both of these mistakes are very rare in China, so that the most violent scenes, such as that of a monk chopping up the statue of Buddha to make a warming fire, never become expressionistic, because the painter restricted himself to the substance of the idea which gave to his forms their own independent life. [ibid. pp. 38-39]

CruelTees® a clothing brand built around sadistic messages

So, what is the relation between the near-homophones statistic and sadistic?

The one, supposedly, a manifestation of pure rationality, drained of emotion, the other a refined and heightened expression of it…

And, still, further or nearer, the relation between state and statist(ic)(al)

The latter often followed by analysis…

Who’s responsible for setting up, and maintaining, the sadist quo?

Let alone, the statist

Quoth the Raven

The uniqueness of Chinese painting, [says Rowley, pp. 28-29] depended in large degree upon the re-working of early principles to meet later needs. In our western civilization, the attitudes and principles of the past sloughed off with each new age; in the Greek development, archaic lines and planes were forgotten except in moments of conscious archaism; and the Renaissance men considered the Middle Ages so inferior that they labeled the art Gothic.

In China alone, new principles of nature and new principles of art were discovered without sacrificing continuity with the past. Suppose Raphael and Tiepolo had retained memories of the spirit and simple directness of Giotto and, at the same time, had conveyed Renaissance “humanism” and the larger unity of the Baroque.[?]

It is difficult for us to imagine such a blending of past and present, and yet something comparable to that is exactly what the Chinese achieved.

…The Chinese shunned extreme naturalism, although, paradoxically, no artists ever spent so much time in contemplating the natural world; on the other hand, they distrusted extreme rationalization, although they insisted, more than any other people, on the value of learning for creative effort. The natural and the ideal were fused together in the ideational “essence of the idea.” As Ch’êng Hêng-lo put it, “western painting is painting of the eye; Chinese painting is painting of the idea.” His statement would have been complete if he had added, “of the idea and not of the ideal.”

The ideal, for Raphael and others of his moment, being precisely not the Gothic. According to some sources Raphael coined the term (in a letter to Pope Leo X) wherein he suggested that the pointed arch derived from the shape made when primitive forest-dwellers bent trees together to form a shelter. Raphael’s sentiment was echoed and amplified by Vasari, who pronounced Gothic Art “a monstrous and barbaric disorder.”

Over time “Gothic” gradually entered into common usage as a general purpose disparagement of both the material production and the unenlightened beliefs and practices of the medieval world. And the concept of the obsolete, even reprehensible, Gothic helped drive a broad-based reconnection with imagined Classical values and modes of representation, articulating a clear separation from the barbarian past, and helping to distance the brave new present from the lurking shadow of the savage, tree-worshippers who had taken down the ideal civilizations of the ancient world.

Ch’êng Hêng-lo’s formulation of western painting as “painting of the eye,” resonates with a passage in Jullien’s This Strange Idea of the Beautiful where he speaks of the “extraversion of sight which has so thoroughly dominated Western painting.”

For Jullien, this extraversion, associated with the creation and enshrinement of The Beautiful, splits into “a feeling of pleasure on the one hand, and a play of cognitive faculties on the other.” Whereas “if satisfaction there is [in encountering, for example, a landscape by Ni Zan], “it is of the order not of sensation (‘of pleasure’) but of internal freeing and soothing.” He quotes the opening of Guo Ruoxu’s treatise: “Each time I enter the empty and silent room, I suspend a roll high up on the white wall and I spend the whole day there facing – withdrawn – and responding to it: radiant as I am, I am no longer aware of the grandeur of the Sky and the Earth, nor of the complications of things; still less am I worried by the eventualities of favor or disgrace in the world of power and profit; nor do I speculate on the chances of success or failure.”

In this meeting ground between human being and painting, subject and object never experience separation. Consequently there is “no longer the gaze but the ‘gathering.’ Gaze or gathering: To what extent do they in fact form an alternative?” [pp. 180-181]

The besotted taste of Gothic monuments,

These odious monsters of ignorant centuries,

Which the torrents of barbary spewed forth.

This uttered, if not spewed, oncet by a certain Molière.

A curious instance of sloughing off and discontinuity with the past, since, as they rippled outward across Northern Europe from their epicenter in Abbé Suger’s Saint Denis, the forms which came to called Gothic were known as “French work,” (Opus francigenum).

The Good, The Bad, and The Gothic

Holy torrents of barbary, Batman!

Well what do you expect, Boy Wonder? This is Gotham.

Proposal to change Manhattan to Gothampton to signify a final rupture with the Lenape past, and bid welcome as the arriviste hordes march triumphant through the flung-open gates…

The image of our time, eyewitnessed in Chelsea this nineteenth day of September, 2016:

Our local plumber (Carl Jumper) in a rainstorm, carrying, in both arms, a shrink-wrapped flat of Poland Spring water bottles.

Look at all you derive out of being alive…

Pressure cookers, flip-phones, wires

Turrorism

The Guiding Principles of Narcissism

The Democracy of Ruins

Landscape with the Rape of Europa, ca. 1670

Graeco-narcissism

Eco-narcissism

Globo-narcissism

Narco-narcissism

Make up yr own!!!

When, after having skirted the first frescoes under the San Marco arcades, stooping before the St Dominic at the foot of the cross, with its immense blue, we emerge at the top of the stairs onto the Annunciation, we are effectively taken hold of, over come, stupefied by this – suddenly prominent – totality of beauty.

These words taken in the literal sense are not excessive, and it would not be going too far to speak of a suffocation that is almost physical. We feel attracted not only ‘through the eyes,’ as the Greeks sais, but also in the pit of the stomach, exactly as though it was the Virgin herself there before us just learning the News.

We did not expect it. Something is uncovered which breaks with the previous time, going beyond calculation, and which we are called upon to confront – or we must close our eyes and renounce it. Is this really a question of ‘pleasure’? If there is satisfaction, there is just as much a feeling of being overwhelmed, because there is suddenly too much to see, the sensations overflow, the sensible has come out of its casing and its limitations and it is now this and no longer the Invisible, which assumes the role of the absolute. [c.f. images of the planes exploding in and against the World Trade Center, the not-so mystic marriage of Annunciation-Apocalypse]

‘Ecstasy,’ the old term used by the mystics, is not out of place since it is really a question, when faced with this beautiful – this completely beautiful, this beautiful brimful – of a visuality which on every side breaks down the narrowness of our gaze, and is strictly speaking exorbitant (as if there was an active side to ‘making the eyes bulge’).

Is this really a question of ‘pleasure’? In any event, there is mingled with it the feeling of lack, that of being unable to respond to this totality of what overwhelms us with its beauty, from every side and with no remission. As it is the totality, it is too much (beautiful) – there is suddenly too much to look at.

How can we be equal to it, to ‘stand the strain,’ as they say, confronted with this torrent of perceptions? Instead of being able to contain these perceptions (that is, maintaining them calmly in their place), suddenly we are submerged in them. Admittedly in order to recover a foothold, one could start to analyse the painting, to break it up, to fix its details, to notice particular aspects of it and even begin to comment on it, but this way would not be convincing enough to allow oneself to evade a tendency to dilute and deaden what had all of a sudden become visibly too much.

When I spend some time on the isle of San Giorgio in Venice, it isn’t long before I can’t take any more of so much beauty – to be continually challenged by this radiant outside, having always to have one’s eyes turned towards it , having the gaze apprehended. The beautiful is literally blinding. [François Jullien, This Strange Idea of the Beautiful, Michael Richardson and Krzysztof Fijalkowski, trans., Seagull Books, 2010. pp. 196-198. Paragraph breaks added by E.D. to facilitate legibility in this format.]

…it took the war to teach it, that you were as responsible for everything you saw as you were for everything you did. The problem was that you didn’t always know what you were seeing until later, maybe years later, that a lot of it never made it at all, it just stayed stored there in your eyes. [Michael Herr, Dispatches. New York: Knopf, 1977]

Holy torrents of perception, Batman!

And the rest is silence history