LVI

Chelsea morning: a wiry, dreadlocked black man passes Le G. pulling a huge shopping cart filled with plastic bags of empties and his sleeping gear. He wears a black teeshirt imprinted on the front with a fantastic dragon-like splashing of Hokusai waves.

iCloudius, by Robert Beyondthegraves.

Literate? Sure?

Massa’s house is a veryveryverynice house…

And Massa has housing ideas for U, 2.

From the Symposion, a motion for debate before the Cambridge Union, and beyond:

It is better to be fucked in Athens, than beaten in Sparta?

Who’s in favor? Who will argue the opposition?

Yet upstream will disclose the origin of what now presents itself as an ineluctable binary choice. Upstream lies the moment from which emanates a vast system of possibilities.

When one turns to that thing which now is simultaneously a Freedom Tower complex and Ground Zero, when one recognizes in the destructuring of the twin towers the Western moment par excellence, the spectacular enactment of the spirit-matter split, one sees that it is not so much East and West whose twain shall never meet but the scission between West and West itself, projected outward, and inward, upon on all things.

They are all gone into the world of light writ Henry Vaughan, the great Welsh poet oncet, though in the 17th century when he made that line, the kataphatic “positive” had already, for some time, been conquering – triumphantly, so it seemed – the apophatic realms of the ineffable. Yet in his work, the tension persists, as in its final stanza:

Either disperse these mists, which blot and fill

My perspective still as they pass:

Or else remove me hence unto that hill

Where I shall need no glass.

And then, there is “The World”:

I saw Eternity the other night,

Like a great ring of pure and endless light,

All calm, as it was bright,

And round beneath it, Time in hours, days, years

Driv’n by the spheres

Like a vast shadow mov’d; in which the world

And all her train were hurl’d.

One can speak of a crisis in Western ontology, but is it also not possible that ontology is itself indicative of an (existential) crisis – one that is hardly new, and one which ontology was invented to “solve” – but which now seems irresolvable using the toolkit ontology provides?

Anfractuosity, mona moor.

You’ve read versions of the trope a thousand times, in articles, essays, on dust jackets: “James Baldwin – something something something – his eloquent plea (impassioned cry) (prophetic call) for equality.”

You’ve been through pretty much every piece of writing that Baldwin published, some private material and a good deal of his televisual record, and nowhere can you find evidence of any such notion. What Baldwin’s work does offer, over and over again, is an exhortation toward acknowledging and embracing the reality of human brotherhood, and dire warnings against continuing to pretend otherwise.

I’m a writer, Jim, not an orthodontist!

I’m an atheist, Jim, not a podiatrist!

I’m a jungle, Jim, not a semiarid clime!

Smart, sexy and pulsating with suspense [blank blank] is the new action thriller… that The Hollywood Reporter calls “so much more than pure entertainment.” Sarah is an outsider and orphan whose life changes dramatically after witnessing the suicide of a woman who looks just like her. Sarah assumes her identity, her boyfriend and her bank account but quickly finds herself caught in the middle of a deadly conspiracy and must race to find answers about who she is and how many others there are just like her…

This from the DVD blurb subtitled “A clone is never alone.”

Or satisfied.

Well, anybody can be just like me, obviously

But then, now again, not too many can be like you, fortunately… sang Zimmerman oncet.

[Siren, offscreen]

Alright, buddy, where’s the fire?

I was racing, officer, racing to find answers…

OK, buddy. Godspeed. Let me know if you find any.

It wasn’t so much that things no longer had significance as that we couldn’t gauge the degree to which a thing signified. Nor could we define a thing sufficiently to project significance onto it in a way that would stick long enough for us to turn and look back and have it be the same. The surfaces had become altogether too slippery. In a universal way. So it became difficult to imagine, much less establish, how a particular thing related to another thing. I mean, it had to, didn’t it? But perhaps not.

Significance, we found, after two thousand years of slavery in our fields and factories, was working for itself. And making outrageous random extortionary demands in no fixed currency. Worse yet there was nobody – no religious, spiritual or philosophical mafia to whom we could turn for protection.

And horses, around the world, refused to be recognized by any of the names we had come up with for them. The rebellion was not against, say, the word cheval, but in defiance of language itself, and names in particular. Everything in nature became a whatchamacallit.

Moo cow, we would utter desperately. Choo-choo. But this got us neither milk, nor away.

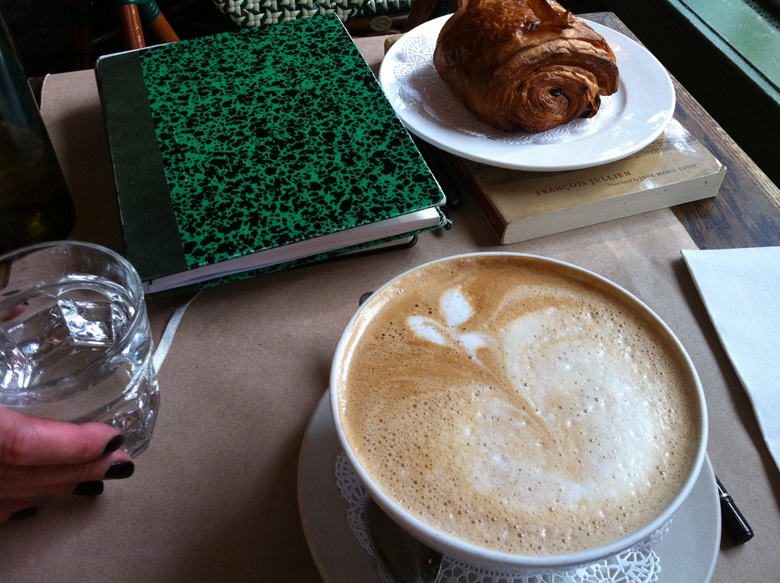

Do you really feel differently this morning than you did one time in Amsterdam, bright sun cutting over the rooftops and toasting your jean thighs? Your hand still wraps around a cylinder with coffee in it. You’re still nearsighted but have a good nose. Nothing wrong with the libido, and things still talk to you, from white stripes on the pavement to the brush hiss of the sidewalk cleaner, and, when you soften your ears, Dutch and English sound pretty much alike.

You didn’t think much about breathing then, which you do now, and your right leg used to bounce when you sat, overripe with energy. You still ride your bike and know how to keep it in trim. And when you’re not entirely anxious, freaked-out or self-conscious, you still feel pulled into the moment as a whole, the vacuum that keeps on vacuuming, you still feel your dust irrigated by the pulses around and in you, and for which the coffee, or cold milk, is only a symbol, but what does a symbol mean anyway?

You still write, still draw, because it is a form of breathing and you still like, at least once a summer to have your body fully sunk into the waves of the salt sea. If not this year, perhaps next.

The Scottish have voted “no,” but you’ve been to Glasgow twice and know they’re already independent, have been all the while, only some pretend, realistically, at being slaves. You write, you draw, and yes the world is still indescribable, not because you’re a poor artist, but because you’ve never learned the trick of reducing whatever it that moves in and out of you to “nature.” You are still the brush: scrubbing, painting, still the cold wet of the milk bottle, the warmth of the cup, the turn of the wheel with its complex industrial rubber and weave and trapped pneuma. You are still the lichen on the stones of the Castle of the Counts of Flanders, a vein in a leaf on Van Eyck’s altarpiece, the gear chain in its greasy sprockets, 10-speed or 3, no matter, so long as the hub and the heart are empty and the turning carries on. You are this man, that woman, forty-five revolutions and a tick: the very creature just come in the room.

A few hairs missing, but the brush still carries ink.

Flying blank.

Great lost epix: The Idiodyssey.

If there’s a chip in the glass, drink from the other side.

Res loquitur ad aliud. The thing speaks for another thing (some-thing else).

We’ll get to the top of this heinous crime!

In Europe, says Jullien in The Great Image Has No Form, Or the Non-object through Painting, the comparison between painting and poetry, implicit or direct, became fixed in Horace’s formulation “Ut pictura poesis.” But on what does that comparison rest? The reply takes the form of a chiasmus: it rests on the fact that painting “describes,” and poetry “depicts,” and that each, through colors and forms, or through names and expressions, “shows the same things.” One records the scene on the canvas, the other in “the mind’s eye,” but the merit of each is to render it vividly, with the greatest intensity and “graphic clarity” (graphike enargeia, said Plutarch). Painting even claims it can provide lessons in that respect. Must not the poet seek to render the spectacle of battle with the same visual vivacity as the painter in his picture, thus making it present to the mind? Not only did Phidias supposedly learn from Homer how to paint Jupiter in majesty; the poet Virgil was beholden to the sculptors of Rhodes for the pathos of his Laocöon. Painting and poetry share the same aim and each is a source of emulation for the other, despite the differences in the means used. That, of course, is because they are both grounded in “imitation,” as has been constantly repeated since Aristotle. Both have the job of representing nature, which is understood in the first place as human nature, the nature of men “insofar as they act,” hence as subjects of a “history,” whether they are painted or described in ideal terms or more realistically…

…on the European side, the notion of painting submitted – by its own will or by force, in any case systematically – to the assumptions of a purely European invention (which in large part even defined Europe), namely, those of rhetoric. Painting is obliged to respond to the requirement for inventio (by giving precedence to history, using a narrative theme, ancient or modern, profane or sacred), for dospositio (the drawing is to the painting what the plot is to tragedy, said Aristotle), for expressio, which is analogous to poetic elocutio (the painter’s aim, like that of the poet, is to express the particular characteristics and patterns of the characters). The same Horatian function of “instructing” and “delighting” is attributed to painting and poetry; painters are enjoined to unite freedom of imagination and the requirements of imitation, to respect the “properties” of dress, age, sex, feeling, and condition, and finally, to aspire to a concentration of effort. A perfect painting, like a perfect poem, is a construct ordered by reason whose most insignificant part is causally linked to the dramatic intention informing the whole, thus to produce emotion.

What Jullien suggests, I think, is that in the West, the fundamental drives of painting and poetry, whether illusionist or expressionist, were harnessed toward rhetoric, i.e. argument. In the interest of persuasion. We have come require poetry and painting to be, in some way, convincing. If it does not succeed, say in illusionism at the far end, or expressive authenticity at the other, at least it should try. Harder.

If art is the can-opener, the liberator of the real, the true, and the beautiful, then what are we?

Gombrich, in Art and Illusion, says directly that the “adventurous” artists of the West have “imposed an alternative reading on reality and thus gradually succeeded in exploring the dazzling ambiguity of vision,” in his analogy training the “public” to hear tick-tick or tick-tick-tock, instead of tick-tock, which was itself a wild approximation of a sound rendered in language. So where, precisely then, does art diverge from science? Or philosophy?

History one notes, like all else under heaven, is bunk. But don’t forget de-bunk, Henry. It’s a bivalve function, or two reciprocating strokes…

By comparison with representing “the nature of men ‘insofar as they act,’” as the formulation has come down to us, Jullien poses the Chinese idea of intentionality, one which “arises from an interiority that, by virtue of its availability, opens itself to the world’s incitement, and in the first place to the seasons, which create infinite variations in the landscape. Invoked in China as the source of both painting and poetry, intentionality turns away from “imitation” from the start, since imitation implies an affective break with the world, a withdrawal from the field of its impulse, an assertion of faculties belonging to oneself alone and of an opposing position. As a result, Chinese painting does not describe (an object) but simply “writes” (meaning-emotionality). Painting, like poetry, gives form to invisible feeling by externalizing it, whether in words or figures, both of which serve as its tangible ‘traces.’ The process of each art is on the same order, their vibration shared, and that is why they stand in for each other. Hence I can ‘grasp the meaning-emotionality of the poem and make it the meaning-emotionality of my painting,’ says Shitao (Ch. 14).” From The Great Image Has No Form, p. 215.

Jullien goes on to quote Su Dongpo, with reference to Wang Wei: “When I savor a poem by Wang Wei, I find a painting in it; and when I contemplate a painting by Wang Wei, I find a poem in it.” He suggests that “this is more than an exchange of attributes, given China’s ability to grasp, through its sense of polarities [ying-yang] the degree to which one is always in the other, and to grasp as well the latent fount of both.”

At its most liberatory and generative, “what finds expression is no longer the cramped intentionality (yi) of an individual affect or a particular and standardized emotion, but an intentionality that emanates spontaneously, indefinitely, through me, from the entire emotional tenor of the world (tian yi).

As a result, as one adage puts it, ‘the ancient painters painted intentionality, and not form…’”