LVIII

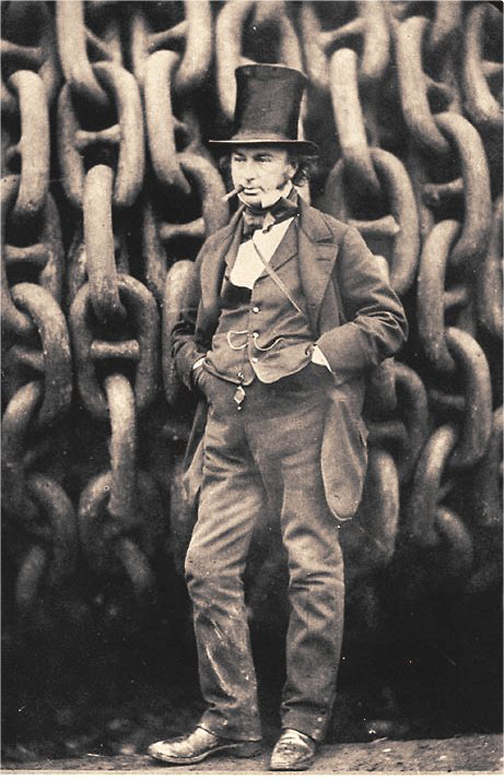

Most good things are being thought of by many persons at the same time. If there were publicity and freedom of communication instead of concealment and mystery, a hundred times as many useful ideas could be generated. Said Isambard Kingdom Brunel, pictured above before the chains of the Great Eastern. Brunel, nineteenth century England’s great civil and mechanical engineer, sought neither patents nor any form of legal protection for his myriad inventions.

Yet, is not the road to, well, where we are, paved with good inventions, however disseminated?

Revolution over easy, or sunny side up? This tromp l’oeil was painted on a Cuban forage cap by Yaima Comas of Ciudad Habana, Cuba. Photo taken by Bronwyn Mills while attending an artists and writers conference in La perla, January 2010. Along with numerous other images using caps as canvas, this huevo was created for an exhibit at the Artisans and Artists’ Cooperative, Matanzas. The caps, a potent symbol of the guerilla struggle against Battista’s regime, were thereafter worn by participants in a celebration commemorating the 52nd anniversary of his overthrow.

The fact is we can no longer afford bad writing.

What happens when we invoke Presence, in expectation that Happiness and Truth will appear?

The work of the West – its gong fu – is a grand historical scheme for the manufacture of lack (absence) the better to construct, vitalize, valorize and worship Presence [qv. Pygmalion and Galatea] via the magic elixir of Love.

But like the alternations of mania and depression which we see and experience in youth, the shocking force of this anti-respiration leads, by degree, and then catastrophically to the uni-polar: the moment of the unfillable abyss.

What is it, then, between us?

What is the count of the scores or hundreds of years between us?

Whatever it is, it avails not – distance avails not and place avails not.

The Way is not distant from us;

When people attain it they are sustained

The Way is not separated from us;

When people accord with it they are harmonious.

Therefore: Concentrated! As though you could be roped together with it.

Indiscernible! As though beyond all locations…

Walt chanted the first three lines in the midst of the 19th century and those succeeding come via the unknown 4th century B.C. author(s) of Nei-yeh (Inward Training), translated by Harold D. Roth in his book Original Tao, New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Mine eleven. Wotta difference anen makes.

In the logic of the English languish, is not a protest antithetical to a contest?

Spellcheck avails not.

Sects and the city.

Waiting for Lofty.

The greatest game, because it is the most deadly: to hold human beings in contempt for being human.

Difference isn’t.

Still, a person could develop a code.

THIS COUNTRY IS NOT AVAILABLE IN YOUR IMAGE

Shekels and the city.

When being and non-being, presence and absence split onto two definitive and defining and mutually exclusive planes, thinking contracts like a severed blood vessel. Story turns miserly. Out of the great truth it becomes the narrative we stuff in our mattresses. As if everything were not everywhere available, we spend only, admit only, think only what we think we can afford.

Christ stopped at Ebola.

Western perception tends toward the unipolar Present, which in turn tends toward the explicit, the fully revealed, the apocalypse, the pornogram. Since the insurrections of the nineteenth century, artists have tried to resolve this bind by deliberately fracturing, dis-figuring, obscuring or “abstracting” the too-explicit figure, in search of a wholeness that is now defeated via another stratagem – a desperate move which does nothing to restore the freedom of the image to emanate from and return to the natural, but only robs it from another direction without shifting the fundamental mode in which it operates.

Too bright, too bright;

It veils not…

What kind of game is afoot when you cannot look into the eyes of the person who made your shoes?

In emptiness lies the potential for generation; that which is full is filled with necrosis.

We decree with full precision and care that, like the figure of the honored and life-giving cross, the revered and holy images, whether painted or made of mosaic or of other suitable material, are to be exposed in the holy churches of God, on sacred instruments and vestments, on walls and panels, in houses and by public ways; these are the images of our Lord, God and Savior, Jesus Christ, and of our Lady without blemish, the holy God-bearer and the revered angels and of any of the saintly holy men. The more frequently they are seen in representational art, the more are those who see them drawn to remember and long for those [holy figures] who serve as models, and to pay those images the tribute of salvation and respectful veneration.

Sayeth the Decree of the Second Council of Nicaea, 787.

Yet the iconophiles and iconoclasts of the Byzantine Empire went at it from more or less 723 to 843 over the purpose and use of religious images. Could a picture fully define a religious being? Should an image be accorded veneration through prayer, kissing and protestation? Emperor Leo III forbade icons in 726 and many were destroyed. In 843, Empress Theodora put her authority definitively behind the iconophiles.

And even Cézanne, who cried Burn down the Louvre! but didn’t attempt it and continually returned to be refreshed at the tainted font, and Picasso who proclaimed it necessary to “kill modern art, and kill oneself if on wants to keep doing something,” could not, with all their superpowers, free themselves, or us, from the single point perspective of seeking a higher truth through invention, through creation, through revelation. Perhaps it was easy for Descartes to say: “In cognition, there are only two points to consider, namely: we who know and the objects that are to be known.” But we have been choking on that phrase ever since, stammering it, barking it, trying to weasel out of its determining lockdown that inheres in every sentence we imagine, much less speak. And, of course, the language-thoughts we ram down others’ throats.

What have our arts done to free us from this condition? What could they hope to effect, deriving as they do from such a long chain of ontotheological concretions, and all-too-comfortably housed within our tongues themselves?

And now, we place our hopes in binary code, the split reductio par excellence of yin-yang to global cubism. Surely something we invent, something we rip out of our heads, will restore us to ourselves.

And then, there is breath, which we do anyway and which need not be forced, breath possessing, as it does, intrinsically, its own intentionality.