CLXXIV

All spokes lead toward and away from the void

What collective predicates make it possible for us to say something like “Walt Disney’s ‘Bambi,’” or “Rockefeller Center,” or “Pericles’ Athens,” or “The Louvre’s ‘Winged Victory,’” without immediately realizing we’re talking nonsense?

What, in short, propertifies our thinking?

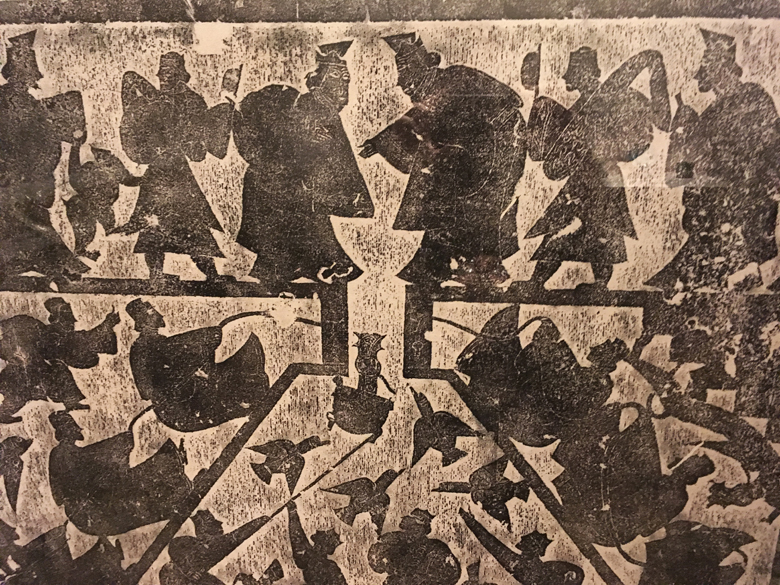

The emperor wishes to recover the tripod – an ancient and enduring symbol of the legitimacy of the state – but the tripod, apparently, has other ideas. The detail depicts the moment when, as the vessel is being raised, a dragon’s head emerges from its mouth and bites through the ropes. As tripod begins to sink back into the depths, the large figures at the top, one of whom is quite probably the emperor, watch helplessly.

“It’s difficult to recognize in this foggy environment the actions that are taking place.” Said Darins Jauniskis, the director of Lithuania’s State Security Department and former commander of Lithuanian special operations forces, speaking of a Russian disinformation campaign. [“U.S. Lending Support for Baltic States Fearing Russia,” NYT, 1/2/17, A3:1]

Wait – who’s fearing what?

It’s difficult in this auto-fog to differentiate objects, subjects, asses, elbows, shit, Shinola®…

Let them eat diamonds

Though there was no first among equals, it was obvious that museum officials felt a special satisfaction about being able to put a face to the name of Mr. [Wilfredo S.] Mercado.

On weekends, he worked as a security guard at the trade center. But in his day job he was a purchasing agent for Windows on the World. His duties included checking that every lobster delivered to the loading dock under the north tower was alive… [“Five Faces, All Immigrants, Are Added to the 9/11 Memorial,” NYT, 1/2//17, A11:5]

The fly becomes the web

Probability: another name for G*d

Lord ‘n’ trailer

Selfie mit bunker

A machine made up almost entirely of ghosts

Manifest density: as u can’t always get watchu want subtly imposes itself as the natural anthem

The dead

The not-so dead

The so-not dead

Risky replaces whiskey

No single malts, blends only

We want no checks

Or balances

Huge white gull

Some days u read the noose,

Some days the noose reads u

[He] set himself to make from another piece of marble a Cupid that was sleeping, the size of life. This, when finished, was shown… to Lorenzo di Pier Francesco [Medici] as a beautiful thing, and he, having pronounced the same judgment, said to Michelangelo:

“If you were to bury it under ground and then send it to Rome treated in such a manner as to make it look old, I am certain that it would pass for an antique, and you would obtain much more for it than by selling it here.” It is said that Michelangelo handled it in such a manner as to make it appear an antique; nor is there any reason to marvel at that, seeing as he had genius enough to do it and even more. [From Georgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, vol. 2, quoted by Andrew Graham-Dixon in Caravaggio, New York: WW Norton, 2010, pp. 383-384]

“Were you on drugs?” Mr. Cuomo asked. “No,” Ms. [Judith] Clark replied. “I was on politics.” [Jim Dwyer, About New York, “She Faced Cuomo and Got Clemency. He Got ‘a Sense of Her Soul.’” New York Times, 1/4/17, A1:3]

A Governor on the Brinks of a…

The Massachusetts Babe Colony

All gaffe, all blooper, all the time…

Constant reinforcement of savage incoherence, unremitting…

Verdant waves of cane

Social life as a rogue algorithm

Is a colonyscope an instrument for diagnosing the state of one’s empire?

Sense of soul

Portrait of Attalos I (?), King of Pergamon; Beginning of the 2nd century B.C.; Marble; ht. 39.5 cm. Discovered in the Byzantine wall on the acropolis of Pergamon.

This portrait, which has been identified as a depiction of King Attalos I (241-197 B.C.), derives from an over-lifesized statue that stood on the acropolis of Pergamon. It is one of the most impressive late Greek portraits that suggest the individual physiognomy of the person depicted while designating him a ruler by means of iconographic devices indicating mood – the wide-open eyes that seem to gaze into the distance, the energetically troubled forehead, and the tensed chin region. The locks of hair across the forehead are rendered in a markedly plastic manner, a feature which probably alludes to the ruler’s posthumous divinization. [Max Kunze, “Classical art in the Pergamon Museum: Past and present,” Masterpieces of the Pergamon and Bode Museum, Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1995, p. 95]

Everybody wants the Dardanelles

It’s hard out here for a primp.

On a warm Wednesday evening in November, Jean Shafiroff, a striking redhead, entered a ballroom inside the Plaza hotel. She wore a custom gown by the Harlem designer Victor de Souza: pink-and-blue striped silk taffeta, with a large bow on the bust and a train so long it could have qualified for its own subway line. Think Jessica Rabbit as a candy-striper [stripper?].

The occasion was a gala for the French Heritage Society [The Proust Ball, no fooling], which seeks to preserve French culture and was attended by a who’s who of counts and countesses. The setting was grand, the music was gay and the Taitinger Champagne flowed like blood from a guillotine…

Ms. Shafiroff exemplifies a new breed of hands-on philanthropist, one who isn’t necessarily born with the right family name, or introduced through debutante balls, or nurtured through the ranks of junior benefit committees. Instead, she is what her husband calls a working socialite, who regards the philanthropy circuit as a profession and is the master of promoting her own image alongside the charities she supports…

At the French Heritage Society gala… there were speeches, a salmon pastrami starter followed by chicken breast and excitement when a party crasher was thrown out by security for trying to steal an armload of the event’s gift bags – a spectacle captured by Lady Liliana [Cavendish] on her smart-phone.

Mr. McMullan, the photographer, stopped to take Mrs. Shafiroff’s picture… Mrs. Shafiroff angled her swan neck and smiled… [“Charming for a Cause,” by Ben Widdicombe, NYT, 1/5/17, p. 1, “Style” section]

Among the musical instruments, the cheng (commonly called gong) is hammered directly from the heated metal without casting; the cho (commomly called copper-drum) and the ting-ning (small bell), however, are made by first casting [the metal] into round pieces and then hammering them.

For hammering the gong or copper-drum the metal is placed on the ground, and the combined labor of many men is required for hammering a large instrument. [As the instrument takes shape] its size is gradually enlarged with the progress of hammering, resulting in the resonant sound of the instrument.

The raised part in the middle of the copper-drum is made first, and then the article is cold hammered to produce the [proper] sound. The slightest difference in the strokes will determine whether the sound will be male or female; the former is achieved with many repeated strokes of the hammer. [Sung Ying-Hsing, T’ien-Kung K’ai-Wu (Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century). Translated and annotated by E-Tu Zan Sun and Shiou-Chuan Sun. Mineola, NY: 1966. p. 197]

Ring dem bellz!

Kvetch your way to rock-hard abs!

Imperative your way to the great conditional…

If I wuz a rich man…

Kvetching and kvetching in the tightening gyre,

Tontocles, the idiot Greek philosopher-hero-general

Tontocracy: rule of the stupid

I was a hands-on socialite for the…

I was a working philanthropist for the…

…How can the artful arguments of the necromancers compare [in their marvels] even to one ten-thousandth of the creations of nature? [Sung op. cit., p. 201]

After his escape from prison in Malta, Caravaggio reached Sicily and sought shelter in Syracuse with his old fellow apprentice Mario Minetti. He was assisted in his research for a commissioned painting, The Burial of St Lucy, by a local antiquarian, mathematician and archaeologist, Vincenzo Mirabella. Among other sites, Mirabella showed Caravaggio “a huge grotto said to have been used as a prison by the ancient tyrant Dionysus. According to local folklore, Dionysus had ordered a deep and narrow slit to be cut into the roof of this ‘speaking cave’, so named because of its extraordinary acoustic qualities, which amplified noise in such a way as to make the least sounds perfectly audible. At the cave’s single entrance, the tyrant built a great gate, so that he could confine his prisoners within. On the hilltop above the cave, perched directly over the slit cut in its apex, he placed the house of his jailor. While his captives languished hundreds of feet below, Dionysus could eavesdrop on their every word. He could hear admissions of guilt, learn their plans, discover the names of their friends and allies.

“After explaining all this to Caravaggio, Mirabella was struck by the acuteness of the painter’s response. ‘I remember,’ he wrote, ‘when I took Michelangelo da Caravaggio, that singular painter of our times, to see that prison. And he, considering its strength, and showing his unique genius as an imitator of natural things, said: “Don’t you see how the tyrant, in order to create a vessel that would make all things audible, looked no further for a model than that which nature had made herself to produce the self-same effect. So he made this prison in the likeness of an ear.” Which observation, not having been noticed before, but then being known and studied afterward, has doubly amazed the most curious minds.’

To this day, the great cave… continues to be known as ‘The ear of Dionysus.’” [Andrew Graham-Dixon, Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane, New York: WW Norton, 2010, pp. 400-401]